A recent article in The Guardian, boldly titled “Humans exploiting and destroying nature on an unprecedented scale”, outlined research that demonstrates that humans are decimating our home with devastating impacts for the other organisms that live on and in it. The planet is struggling to support the excess consumption of billions of people who, primarily within the developed, industrial world, have created a culture of materialistic desire and consumption. Whilst there is an abundance of research and articles that detail the radical next steps we need to take to fix this disastrous trajectory, there are few that look back to understand how we got to this stage. Is this an inevitability of our brainy species, the ‘superior’ inheritors of the Earth?

Humans exploiting and destroying nature on unprecedented scale report aoe

Many people might be quick to say “yes” to this question; after all, we’ve been spun the narrative that Homo sapiens is a unique species that have succeeded where so many of our evolutionary cousins have failed. But it is this very narrative that is the problem, and that perhaps legitimizes some of the actions we take today, and by “we” I almost exclusively mean those of us living in large-scale, industrial societies. Somewhere in the history of our society, we have created a palatable story that we’re evolutionarily entitled to wreak havoc on the planet. I would argue, from an anthropological perspective, this has been fueled and perpetuated by a gross misunderstanding of our origins and evolution.

Somewhere in the history of our society, we have created a palatable story that we’re evolutionarily entitled to wreak havoc on the planet. I would argue, from an anthropological perspective, this has been fueled and perpetuated by a gross misunderstanding of our origins and evolution.

This idea of our species’ superiority is rooted in early perspectives on human evolution. Darwin’s seminal books On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871) coincided with the earliest discoveries of the antiquity of humans, most notably the discovery of a Neandertal skull from the Neander valley (Germany), first recognized as a different hominin species by Lyell’s (1863) The Geological Evidences for the Antiquity of Man. Enlightenment thinking, one of the founding principles of 19th Century European society, formed the basis for how these new ideas about human origins were received. A key component of Enlightenment thinking emerged from classical physics: the universe is mechanical, governed by natural causal laws, and divided into Cartesian binary oppositions such as human/animal, mind/body, and nature/culture.

Perhaps as a consequence of this thinking, or to make the idea of human evolution more palatable to people unacquainted with these Darwinian ideas, early discussions of human evolution cast it as a progressive march towards the exceptionalism and superiority achieved by 19th Century society in the Western world. Neandertals were portrayed as the opposites to Homo sapiens, becoming the brutish evolutionary cousins incapable of the sophisticated behaviours of Homo sapiens such as language, complex technology, or art. Comparisons were also drawn between the “primitive” stone technology of early humans, and the technologies of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, and served to legitimise colonialism: industrial societies of the 19th Century perceived themselves as having escaped this “barbaric” past, whilst hunter-gatherer societies were “frozen” in this way of life. The idea that contemporary, industrial society was the pinnacle of a linear process which had been ongoing for millennia became a belief rooted deep within 19th Century Western worldviews, even replacing religious creationist beliefs (McNabb 2012).

The idea that contemporary, industrial society was the pinnacle of a linear process which had been ongoing for millennia became a belief rooted deep within 19th Century Western worldviews, even replacing religious creationist beliefs.

Whilst post-modernist thinking has sought to challenge these foundational ideas of a mechanical universe that is divided into binary oppositions, these 19th Century ideas of progression still form a key part of how many people in developed, industrial societies perceive the world: humans are separate from nature and dominate it. But the climate crisis has brought into sharp relief that we are not; our impact on the environment and the devastation caused to towns and cities by extreme weather conditions demonstrate the entwined and delicate relationship we have with nature.

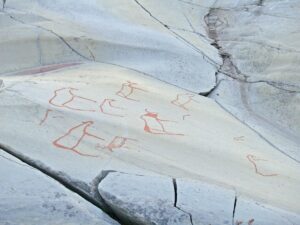

Anthropological perspectives on human evolution further challenge the anachronistic idea of human superiority and linear progression narratives. For example, we now know our close evolutionary cousins – the Neandertals – were likely equally cognitively capable as us, producing complex tool technologies and even art. We were not a superior species, that solely caused the demise of the Neandertals by outwitting them; instead, it was likely a myriad of distinct, complex environmental, social, and demographic processes. Whilst the reason for our species’ survival is hotly debated, the idea that we survived because we were “better” or “more evolved” is now long outdated.

Ethnographic studies also show just how W.E.I.R.D (a clever acronym for Western Educated Industrial Rich and Democratic people, first coined by Henrich et al. 2010) these perspectives are in developed, industrial societies. Many small-scale societies often have the deep-rooted understanding that they are fundamentally the same as other living beings in their world; they do not perceive themselves as superior to nature, but a participant in a shared natural world. The depth of this understanding within these societies may be due to their lifestyles. Although this is certainly an over-simplification of the non-generalizable diversity of these societies and their ontological understandings, it does serve to shed new light on our own lifestyles and worldviews.

Anthropological perspectives on human evolution further challenge the anachronistic idea of human superiority and linear progression narratives. For example, we now know our close evolutionary cousins – the Neandertals – were likely equally cognitively capable as us, producing complex tool technologies and even art.

For us in the industrial world, it seems we have diverged from the understanding rooted in small-scale societies, through portraying ourselves as the pinnacle of evolutionary processes and legitimizing our disastrous lifestyles. Our degree of separation from the natural world has placated us. We are no longer sensitive to the devastation caused by our overconsumption, creating an alternative reality where we place plants and animals as subservient to our own needs. Consequently, we happily continue to consume and destroy to fuel our ecologically disastrous lifestyle, perhaps because we are merely unaware of the true consequences of these actions.

So, what can the anthropological perspectives briefly presented here offer to us in large-scale, industrial societies, with our materialistic, consumption-driven lives? And can we even radically change our lifestyles, to be more akin to those in small-scale societies? Whilst our entangled dependency on materials might be an irreversible consequence of our large societies, as the archaeologist Ian Hodder (2012) argues, we can still challenge those foundational perspectives that have led us here. A shift in our thinking, to realise we are an intrinsic part of this world and not dominant to it by virtue of some arbitrary measure of superiority or progression narratives, might be a good place to start. The world is not ours alone, and we must learn to appreciate and share it with our fellow species. Several commentaries on the climate crisis have emphasised the importance of us “returning to nature” and appreciating that we are part of an interconnected web of life. If we learned to perceive ourselves as participants, rather than at opposition to the natural world, it is likely we might be more sympathetic to the crisis facing our, and every other, species.

A shift in our thinking, to realise we are an intrinsic part of this world and not dominant to it by virtue of some arbitrary measure of superiority or progression narratives, might be a good place to start. The world is not ours alone, and we must learn to appreciate and share it with our fellow species.

Bibliography

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J. and Norenzayan, A. (2010) ‘Most people are not WEIRD.’ Nature 466: 29.

Hodder, I. (2012) Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

McNabb, J. (2012) Dissent with Modification: Human Origins, Palaeolithic Archaeology and Evolutionary Anthropology in Britain 1859 – 1901. Oxford: ArchaeoPress

Izzy Wisher is an archaeologist, specialising in interdisciplinary approaches to Palaeolithic art. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Aarhus University (Denmark), working alongside cognitive scientists on the ERC project eSYMb: The Early Evolution of Symbolic Behaviour. She completed her PhD in 2022 at Durham University (UK), where she used virtual reality and methods from psychology to understand how pareidolia – the phenomenon of seeing forms in random patterns, like faces in clouds – influenced the production of Upper Palaeolithic cave art in northern Spain.